A Dragonfly in the Rainbow?

A discussion on Brian Chadwick, the disappearance of his DH90A Dragonfly ZK-AFB in 1962, and reports of aircraft debris in areas near Mt Aspiring.

This website consolidates the observations of numerous people relative to the Rainbow Valley near Mt Aspiring, and presents the case for there being aircraft debris on the eastern slopes of that valley, more likely than not from the Dragonfly. Most of those named here have been personally interviewed. All are assessed as being highly credible.

The disappearance

Much has already been written about this aircraft and it’s disappearance in 1962. The definitive history of Chadwick, the disappearance of his aircraft and the extensive search for it, has been thoroughly set out in the Rev Dr Richard Waugh’s superb 2005 book “Lost...without trace”. Richard dedicated his book to the memory of the five people killed in this tragedy.

The Dragonfly piloted by Brian Chadwick with four tourist passengers left Christchurch on February 12th 1962 bound for Milford. There were two route choices - via the West Coast (the preferred usual tourist route), or alternatively east of the Main Divide whenever access to the West Coast was blocked due to bad weather in the mountains. The Dragonfly disappeared. After it left Christchurch there were no officially accepted and confirmed sightings of it again. It was largely believed to have crashed either in the mountains or in bush, somewhere south of Christchurch. Considerable resources were put into the search effort but the volume of reported sightings and hearings was such, especially on the West Coast, that search authorities were faced with an overwhelming task. It developed into what would become the most extensive aerial search in New Zealand aviation history.

Aerial searches were carried out by fixed wing aircraft as helicopters were rare in New Zealand in 1962. Much of the search effort was directed at the West Coast. On the day of the disappearance the West Coast weather had been good but the ranges were described by one very experienced mountain pilot as being “pitch black”. The search was given up before many areas on the east side had been well covered and weather and other factors prevented more extensive searching of the Aspiring area.

The DH90A Dragonfly

In 1962 this was a more than 26 year old aircraft, a twin engined bi-plane with a wingspan of over 13 metres and a 9.6 metre long fuselage. It was imported into New Zealand, new, from the UK in 1937. Designed by de Havilland, it had been built as a luxury touring aircraft aimed at the wealthy private owner market. It was the last biplane de Havilland designed and built.

Geoffrey de Havilland had an intense interest in natural history, particularly entomology, and named many of his aircraft after insects. The Dragonfly’s fuselage was a monocoque shell of fabric covered pre-formed plywood with a cantilevered undercarriage and welded steel engine bearers. The two Gypsy Major engines drove twin-bladed wooden propellers.

This Dragonfly had some potentially serious technical issues relating to carburettor icing in one engine and an inability to stay aloft on one engine particularly at high altitude. When it left Christchurch the aircraft had been overloaded, with considerably more fuel than permitted. It had earlier been equipped with a Magnetic Compass however Chadwick had replaced that with a Radio Compass, a move later criticized by some engineers and pilots. One said that the new Radio Compass had limited range and in mountainous country would be virtually useless. Another said that to not take a Magnetic Compass while flying in the mountains was - “beyond dangerous and stacking the odds up really high as you never knew when you might need it”. Some who knew the aircraft well, later expressed the opinion that it had been an underpowered aircraft totally unsuitable for mountain flying.

Chadwick

Chadwick himself described the New Zealand alps as the trickiest he’d found anywhere in the world, and said that there had been several occasions when he found himself fully committed in shocking weather. In a conversation with a fellow pilot, Chadwick mentioned some flying episodes that his colleague thought would have been hair-raising. Chadwick talked about how his passengers just didn’t know the risks he took for them. He described how he was once forced during a flight to Milford to make a difficult landing in Queenstown after being in cloud and running seriously low on fuel with ice coming off the propellers, knocking holes in his aircraft. Chadwick was observed after that flight as being in such a state that he could not hold a cup of tea. His nerves were completely shot and he spoke in a fatalistic way about how he expected to be killed on these flights.

Chadwick firstly trained in the RAF as an aeronautical engineer though in 1941 commenced some flight training. He came to New Zealand in the early 1950’s, looking for opportunity.

By the time of his disappearance Chadwick had had an extensive flying career, not only in New Zealand, and had carried out more than 150 tourist trips from Christchurch to Milford return. He was an ex-RAF Squadron Leader and a very experienced pilot. He was also ambitious. He’d once told an American interviewer that he had hopes of building a nation-wide tourism airline in New Zealand.

Chadwick had been described as having an adventurous spirit. One person who knew his flying well thought he was a little foolhardy. Following the disappearance someone else who knew him well said that he thought Chadwick and his southern flights in the Dragonfly had been an accident waiting to happen.

One pilot thought Chadwick a likeable chap but who's style of flying led him to believe that Chadwick was not a safe pilot and definitely not an alpine pilot.

These were thoughts on Chadwick by some of the people who knew him well professionally and are only mentioned here as being, perhaps, relevant to what might have happened to Chadwick and his four passengers. Beyond that though, Chadwick deserves to be remembered for his courage, entrepreneurship, and huge contribution alongside his friend and fellow Brit pilot Brian Waugh, in pioneering a new era in New Zealand aviation tourism.

The West Coast/East Coast debate

There has always been confusing speculation on whether or not Chadwick managed to get this aircraft across the Main Divide to the West Coast, despite tangible evidence, historic and more recent, indicating that he didn’t.

Recent interviews carried out by phone and email now provide a compelling accumulation of evidence confirming the official 1962 SAR belief that this aircraft never got across to the West Coast. This new evidence is comprehensively detailed in a research document which can be downloaded by clicking on the link Mackenzie Route Paper.pdf in the top navigation menu. This provides sound evidence for an eastern routing, including clarification of some earlier reports and their interpretation at the time.

One highly credible report reveals the aircraft being seen entering Huxley. A later report came from Dingle Burn, which leads directly to Lake Hawea, across from Aspiring.

All of this now provides overwhelming evidence that this aircraft never got across to the West Coast, despite Chadwick attempting to do so at a couple of points.

On the day, Chadwick told Christchurch airport authorities that the Mckenzie Country was the route he had to take because of the weather. Additionally, he even wrote down on his submitted Flight Plan that Queenstown (abbreviated by Chadwick on the Form as “QN” ) would be his Alternate Aerodrome. That handwritten notation is an important piece of supporting evidence, never previously commented on, of his intention to take a route east of the Divide and not via the West Coast.

Reports & Observations 1962 to 1972

Mt Aspiring Station - 1962

Mt Aspiring Station is an historic farm property situated at the confluence of the East and West branches of the Matukituki River, with both branches originating from tributary streams running from six glaciers surrounding Mt Aspiring. The Station has been farmed by the Aspinall family for over 100 years. In 1957 they voluntarily surrendered 50,000 acres (20,235 hectares) of their station to the Crown, to help form what is now Mount Aspiring National Park.

Several people at the property who were familiar with routine aircraft activity around Aspiring, including Phyllis Aspinall, reported clearly hearing an aircraft around noon on the day of the disappearance, circling for 10 minutes high in or above thunderous cloud. On that day in February 1962, and at that time, there had been no known aircraft other than the possibility of the Dragonfly in that area. While never sighted, that aircraft was never heard or seen again, or otherwise accounted for, which consequently leaves the overwhelming thought that it perhaps never left the area.

Phyllis Aspinall - by phone in 90’s

Mrs Aspinall confirmed that she heard an aircraft circling around Aspiring, in what she said was “thunderous cloud”. She also confirmed that several station hands heard the same thing. Nothing however was ever seen.

Paul Powell, mountaineer & author - 1962 (by phone in 90’s)

Some people professionally involved in the search believed that the Aspiring area was one of strong possibility. Paul Powell, a very experienced mountaineer who had climbed extensively in Mt Aspiring country, was the Chief Search and Rescue Officer of the New Zealand Federated Mountain Clubs in the Otago region and was heavily involved in the search effort. Powell was forever convinced that the aircraft came down in the Aspiring/Matukituki area, as were his SAR colleagues. He knew of the Aspiring Station hearings and felt very sure that the aircraft had come down in that region. Some close colleagues of his felt the same. Powell was a Dentist by profession, a poet, and an author of several books including his classic book on climbing - “Men Aspiring”. In a chapter he devoted to the disappearance of the Dragonfly, Powell said - “I have a feeling, so strong that it has returned to me time and time again over the years, that the Dragonfly is somewhere near Aspiring.”

After the official search was called off Powell spent much time searching for it on foot in areas above both branches of the Matukituki River and also, perhaps interestingly, in an area east of Rainbow Valley where he later had the New Zealand Geographic Board name a nearby peak after the Dragonfly.

Interesting sketch from Powell's book "Men Aspiring" showing the Dragonfly flying through Rainbow Col

In his book“Men Aspiring” Powell recalled that -

- At Mt Aspiring homestead the mountains were covered in cloud above 6000 ft, though there was little wind.

- An aircraft was heard for 10 minutes above the clouds.

- Phyllis Aspinall heard the aircraft quite clearly from inside the homestead.

- A station hand behind the woolshed heard it flying in the direction of Niger.

- It was heard at about 11.50am, for 10 minutes, from the hillside above the old MacPherson homestead.

SAR HQ opinion

Controllers at Search HQ in Christchurch had also regarded Aspiring as an area of high likelihood. At that time, on that day, there was no other aircraft identified by Otago or Christchurch HQ search authorities as operating in that area.

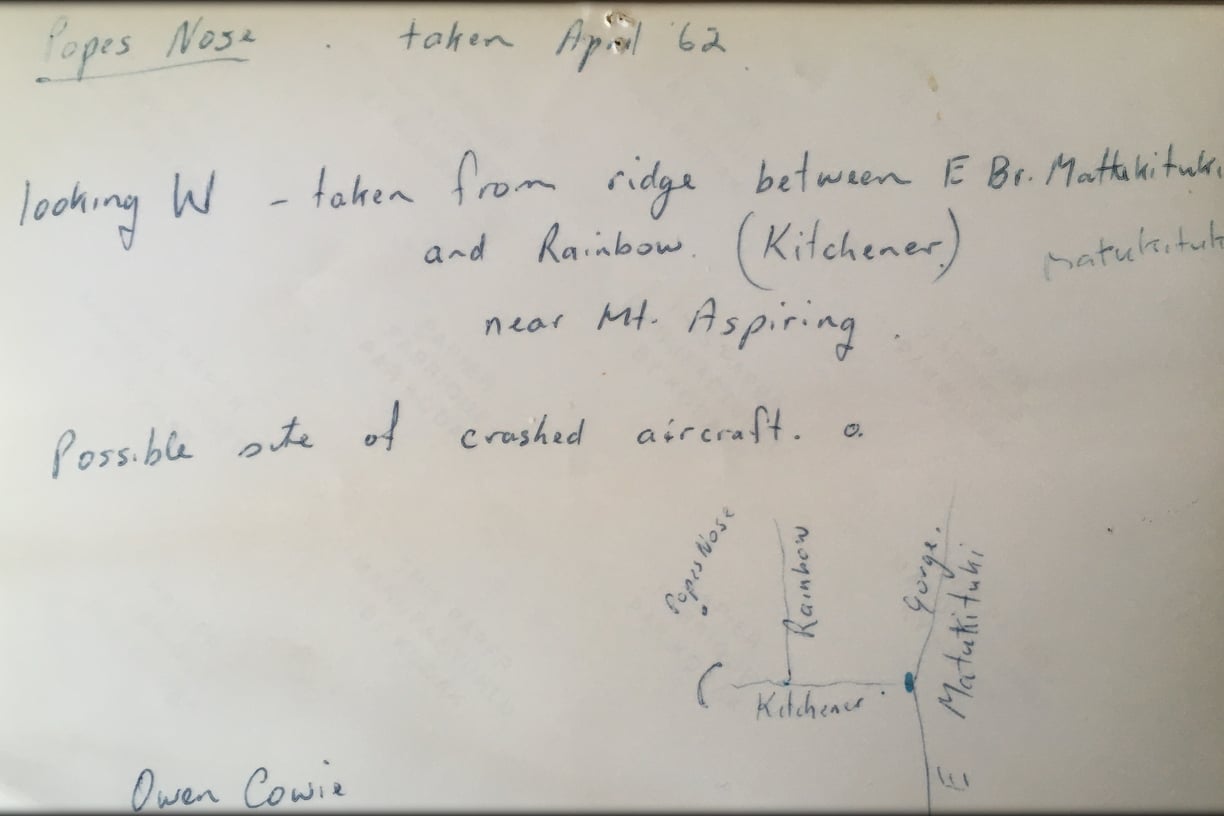

Cowie & King, hunters - 1962 (personally interviewed in the 90’s)

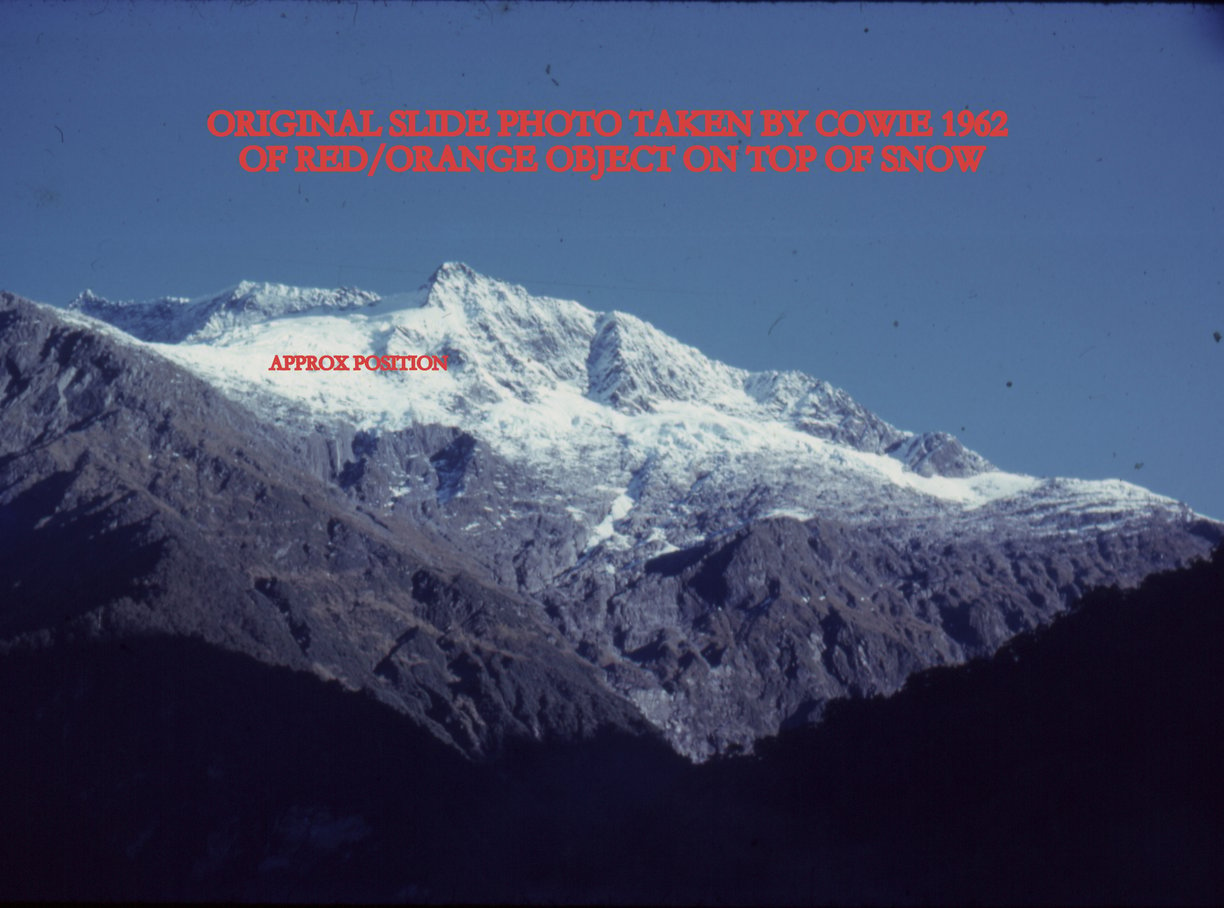

Two men, Owen Cowie and Bryon King, reported seeing something just six weeks after the February 1962 disappearance. They had been hunting on the tops on the east side of Rainbow Valley near Aspiring, in April. They both saw a red/orange coloured object lying on the snow in the vicinity of Kitchener Glacier. They thought it had a metallic appearance. Unfortunately, at the time the men weren’t aware of the aircraft’s earlier disappearance. Some months later they overheard someone at their tramping club talking about it and then realised the possible significance of their sighting. Cowie was told later by the tramping club member that the area had in any case been well searched and that Cowie was therefore wrong. In fact, the area had not been well searched whatsoever. Their sighting, and what they had to say about it, was never actively followed up, until 1992.

Owen Cowie's sketch

There could be no natural reason for something of that description to be on top of any glacier, particularly in 1962. It could only have come from an aircraft; there can be no other rational explanation for it. Cowie had taken a photo from where they were standing but unfortunately the slide image wasn’t clear enough to identify the object. He also drew a map of the area where they’d seen the object.

Both men revisited the area with the writer in the 90’s. Kitchener Glacier was flown over in 2023 and it was notable that any object that may have dropped on to it on snow could never remain on it long and would have been very soon after taken down by snow and glacial runoff into the rugged gullies immediately below.

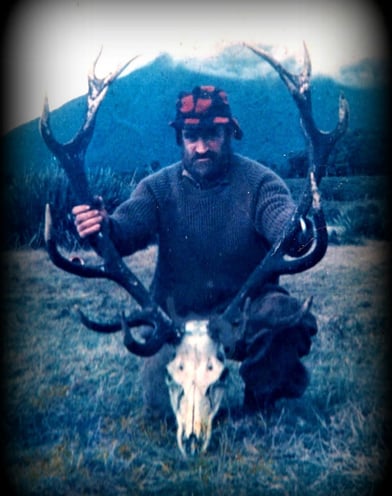

Bob Gibson, hunter - 1963 (personally interviewed in 90’s)

In November 1963, 20 months after the disappearance, another hunter, a professional one named Bob Gibson, saw something in that same area but on the eastern side of Rainbow Valley. Deer had been a pest since the 1930’s, destroying native plants and trees and causing erosion. The government decided to reduce their numbers by engaging hunters known as deer cullers. The cullers worked in remote areas, living in huts and using their eyes for a living. Bob was one of those. He was in Rainbow Valley with a shooting friend, Ian Reinke, hunting deer. Bob saw the sun shining on something on the eastern slopes and reflecting back. He thought it unusual and tried to check out the reflection using his rifle’s telescopic sight. At first he thought it might have been a waterfall as the east slopes have many ravines and watercourses but he quickly discounted that due to his knowledge of the terrain. He decided to check it out and using his bush navigation instincts made his way up to where he had seen it. He arrived at a high point where he was able to look down and saw where a beech tree had had its top snapped off. Below it, another tree also had its top snapped off. The breaks appeared relatively fresh but were not natural and were completely out of keeping with anything he’d ever seen before in the bush. He was left to conclude that something had come down on an angle and hit them. He attempted to get down to them but couldn’t. By then it was getting dark and bad weather, so typical of the area, prevented any searching the next day. The men then left the area and Bob soon after went deer culling in the North Island and never returned to the Aspiring area to hunt.

Gibson had spent many years in the mountains. He’d buried caches of ammunition and supplies in areas that he expected to return to one day. In 1992 Gibson and his 1963 companion Reinke agreed to be flown back in to the area where Gibson did his best to try and identify the area where he’d seen this.

Note - Cowie and King also agreed to be separately flown in later, to do the same thing. In the opinion of the writer who went with these men and spent several days with all of them, their stories are 100% credible. Gibson was a well known professional hunter. His account, still supported today by his companion Ian Reinke, is assessed as being highly credible. These were no-nonsense tough individuals who separately but between them had seen something very unusual.

Alan Duncan, hunter & helicopter pilot - report from 1972

Alan Duncan has been described as the best hunter New Zealand has produced - a legend among those of his generation who professionally stalked New Zealand’s high country. He was said to apply himself to hunting with a single-mindedness that bordered on the ruthless. A distinguished New Zealand writer and former deer culler described Duncan as good at anything he turned his hand to, yet remaining a modest man who never concerned himself with status. He was a man of few words but great action.

Duncan once casually mentioned to Bradley about how, in 1972, he’d been piloting a helicopter and chasing a stag near the northern end of Rainbow Valley. Rotor downwash from the hovering helicopter disturbed bushes and revealed what Duncan described as “a silver wing ” - in Duncan’s adamant opinion, part of an aircraft.

Duncan later began flying, firstly with fixed wing aircraft and then helicopters, hunting for Sir Tim Wallis’s deer operations out of Wanaka. In later years he and his wife moved to Geraldine, then on to Pleasant Point near Timaru from where he continued hunting with a friend, Brad Bradley.

Missing 1962 Otago SAR Search Log

There are several references in Powell’s book “Men Aspiring” to Powell and colleagues Ross Lake and Bruce Moore making entries into a search log maintained locally by them at the Dunedin (Police) Operations Room over a period of seven days. Powell mentions it as being “wrote up”. The log may have been written up by hand by them, or more likely typed up by Police personnel. It is quite separate from the main log, maintained and typed up at Search HQ in Christchurch in 1962 and still available.

Recent searches of Police and Dunedin main archives, and enquiries with respective families, have so far failed to locate that Dunedin search log. It has never been examined or commented on and is probably still lingering somewhere in some Otago archive, possibly even amongst Powell's private papers now held at Dunedin Archives.

In March '62, a few weeks after the disappearance, Powell and Bruce Moore carried out the first ascent of what was later named Dragonfly Peak. Powell later personally searched areas around the north branch of Albert Burn, just east of Sisyphus and Rainbow Valley. Might that Dunedin log contain local reports that were never passed on to Christchurch Search HQ? Powell later quit his SAR position due to his frustration over equipment needs. His conviction that the aircraft came down somewhere in this area might possibly have derived from more than just intuition.

Secondary supporting accounts - 2023

Alistair (Brad) Bradley - personally interviewed 2023

Brad Bradley, a recreational shooter, met Alan Duncan after Duncan moved to South Canterbury. Duncan told Bradley about what he had seen in 1972. They spent time on Google Earth and Duncan pointed out an area on the Rainbow eastern slopes. He described to Bradley how he and his shooter were chasing a deer uphill, with (to quote Duncan)“a shitty gorge” running parallel to the helicopters right side. Duncan said that what he’d seen looked like a wing.

Bradley describes his late friend as having been a man of few words, who shied away from attention and who thus somewhat characteristically never gave the incident more thought, or bothered to report it. At Bradley’s instigation, the two men spent time together on Google Earth to identify the area within Rainbow Valley where Duncan saw this object.

Mark Duncan - Alan Duncan’s son - (by phone 2023)

Alan Duncan once mentioned the sighting to his son Mark. He described how something had caught his eye when going up a valley. (Mark thinks his father might have been piloting a Hughes 500 in which case he'd be sitting on the left). He said he saw something shining in the scrub. He thought it was possibly perspex. Mark says his father used he word “perspex”, and described it to Mark as “a reflection - something shining back” towards him.

Allan Wilson - (personally interviewed 2023)

Wilson had known Duncan since their early deer culling days in the 50’s and 60’s - some 60 years. At one stage each of them owned Piper Cubs. They went to all the deer culler reunions together, and camped together. Wilson felt that he knew Allan Duncan better than most.

Wilson had flown both rotary and fixed wing aircraft. The two were talking one day about aircraft. In passing, Duncan mentioned what he’d seen in 1972. Wilson clearly recalls Duncan saying that it was “a reflection”, and “could have been a piece of grey slate, or an “aluminium” wing, or even “perspex”. Wilson clearly recalls Duncan saying - “it looked like a bloody aircraft wing”.

In Wilson’s experience, for rotor wash to have any effect Duncan would have had to be flying low down and right on top of the animal, which because it was being chased would have been heading into the wind.

Wilson said that Duncan and his shooter would have to have been in reasonably open ground, and at their rate of speed Duncan would have only been able to get a fleeting glimpse of the object.

Wilson said that Duncan was a very hard man to get stuff out of - very close. But was one of the most sincere men Wilson had ever met. They shared the same background in deer culling, venison recovery, and aviation. Duncan “never wasted his breath on pointless conversation”. He enjoyed his own company and had little to say most of the time. His shooter Bob White once told Wilson that he and Duncan would meet at the helicopter in the morning and very few words would be exchanged over the whole day; they had a job to do and they just concentrated on doing it.

Wilson said that the people who knew Duncan would all agree that if Duncan told them anything it would be one hundred percent correct and one could depend upon it. In Wilson’s strong belief, if Duncan said he saw something unusual, then he did.

Wilson referred to a lengthy magazine article written about Duncan after his death. It mentions how Duncan rarely talking about himself, or his work.

In considering the Rainbow terrain, Wilson wondered whether - with no deer grazing and a warmer climate - after 60 years the above-bushline area in which Duncan had seen this might by now have more tree cover, with today’s bush line now being higher than it was in 1962?

Ian Reinke - (personally interviewed 1990’s and again 2023)

Reinke was Gibson’s hunting companion in 1963. He described, now assisted in 2023 by high resolution photographs, how they we were sitting on tussock in the afternoon looking at the tops of the eastern slopes across the valley and saw something “shining back” straight ahead, directly opposite to where they were. The sun was roughly to their back.

Reinke says that Gibson thought it highly unusual and firmly believed it could not have been ice as there was none up there, nor rocks with minerals that might shine, nor snowmelt.

Reinke described how Gibson went up alone to investigate, with Gibson circling up and around and once at the spot looked down and saw a near-dead tree, by itself, just on the edge of the bushline. The top was broken off. Gibson was adamant that it was a fresh break. Gibson walked down into the trees and about quarter to half-way down found another tree with its top freshly broken off.

Gibson searched the immediate area but it was by then getting dark in the bush. Deteriorating weather prevented any return and the two men had to leave on the next day.

Reinke said that Gibson thought what he had seen might have been glass, or an aluminium frame.

Note - Possibly important to search planning, Reinke wonders whether this object may have had to have been on a ridge or other high point in the terrain, in order to have been visible from where they’d been sitting, down by the valley floor?

Reinke and Gibson returned to the area with the writer in the 90’s. And again not too long after when they actually found the top tree, and photographed it. Over the intervening years, that particular photo has unfortunately been lost.

Greenlees party - Spar discovery and possible fuselage sighting - 2004

Richard Greenlees of Christchurch is an internationally renowned clinical dental technician, and a nephew of Ian Reinke. Reinke had been telling Greenlees about Gibson’s sighting in 1963, and it took Greenlees’ interest.

In 2004 Greenlees privately funded a search back in there. He was accompanied by two friends - Jeremy Harnett an Environmental Scientist, and photographer and businessman Hussein Burra, and Reinke. The four men set up camp on the valley floor and then spent several days searching an area on the eastern slopes as pointed out by Reinke.

Greenlees found the terrain very rough, describing some of it as dangerous. This made their overall search endeavour somewhat exhausting, particularly near the end.

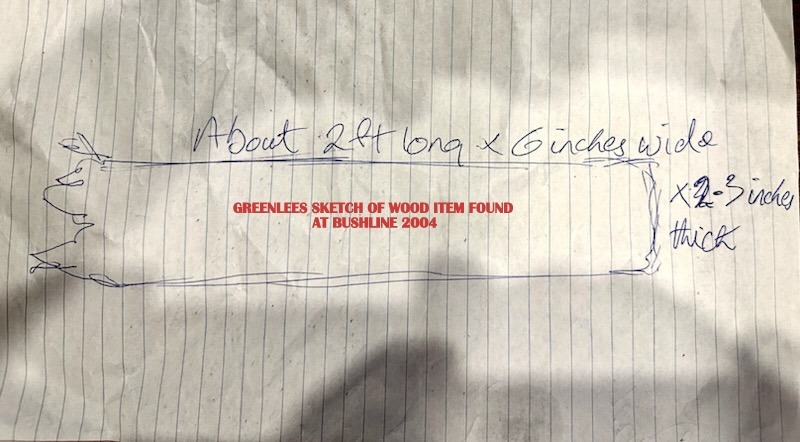

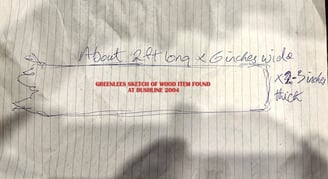

Possible Stub Plane Spar find

On their last day, while searching in an area near the edge of the bushline, Greenlees & Burra came across a piece of wood. They examined it and remain absolutely adamant that it was an "engineered" item - manmade. It unfortunately wasn't photographed and after considering taking it back down, the object was left there.

Greenlees initially described it as - "under half a metre long, maybe 8 inches thick, and about close to 2 inches thick.” Later, on request he made a rough sketch of it -

Greenlees describes the wood section as straight, and “silvery” as if it had been exposed to sunlight on the bushline edge. After deliberating on it, the two men decided to discount it - a decision Greenlees now regrets but they were in a state of some exhaustion after several days searching and in a hurry to get down to helicopter out.

Of course neither of these men had any familiarity with the construction detail of de Havilland aircraft. A stub plane spar in a de Havilland Dragonfly is a machined timber beam, typically made from Sitka Spruce timber. (Note - one Google reference on Sitka Spruce says that - “on exposure to the elements, its colour darkens to a silvery-brown tinged with red”). The spar runs at a right angle out from the fuselage and into a wing section and provides the majority of the weight support and dynamic load integrity of the aircraft. During flight it is subject to various bending and load forces.

Colin Smith of the Croydon Aircraft Company at Mandeville Aerodrome near Gore has expert knowledge of a DH90A’s construction. He advises - “There is only one wooden part of the Dragonfly that could possibly be of the width and thickness you indicate, would/could be part of the stub plane. It is really the spar which the whole centre of the aircraft is built around. It is made of several pieces, and one of these pieces is approx. of that width, i.e. 8” by 2” thick and its total length is much longer, than under ½ metre. The constructed spar is nearly 4 metres long.”

Spar find location

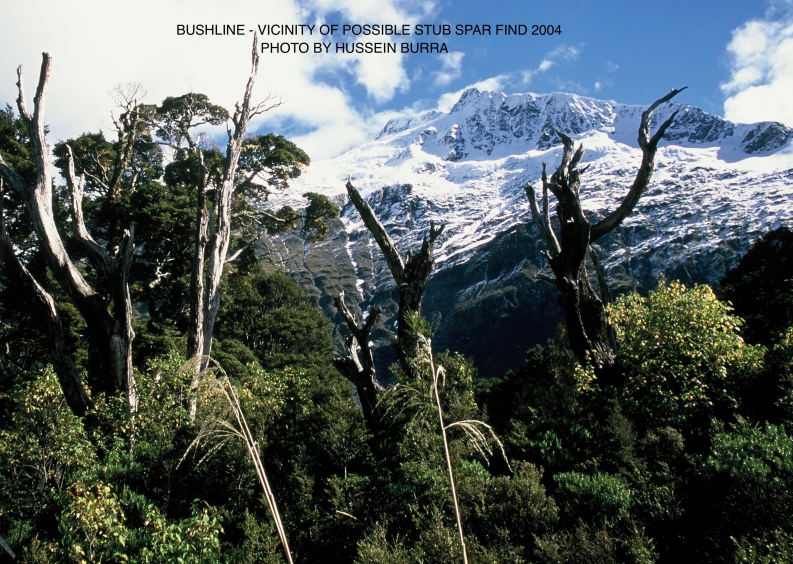

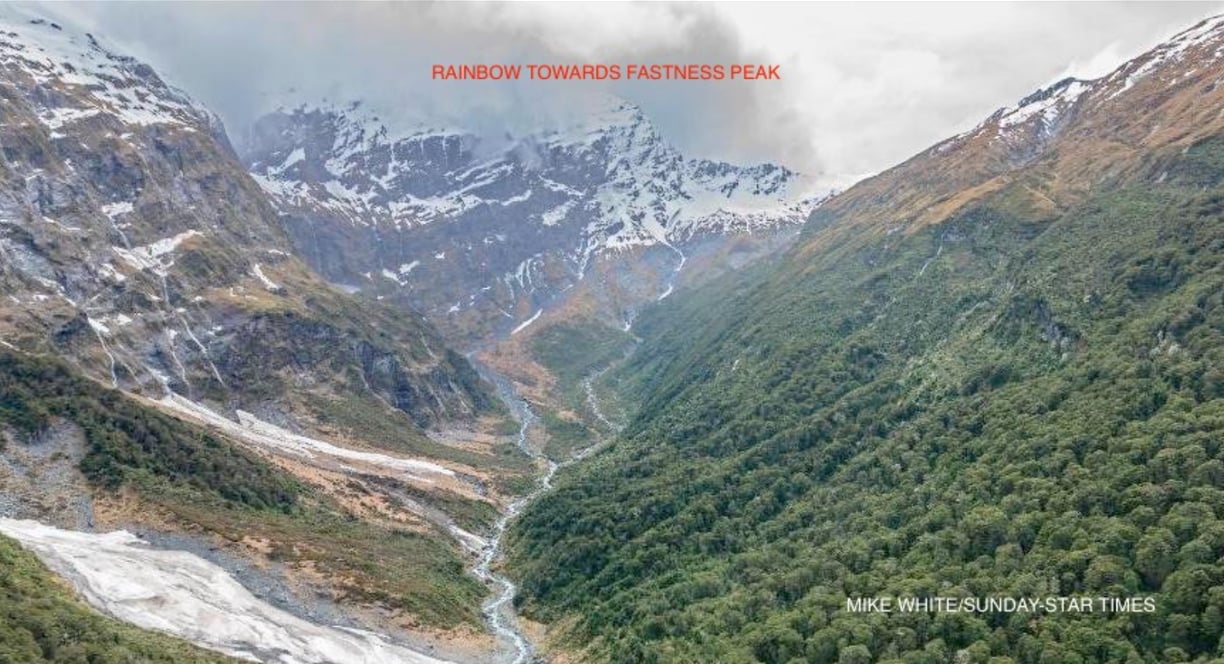

While the timber object was unfortunately not photographed, Hussein Burra did however take a photograph of the general area they were in at around that time, just by bushline -

The high quality of this photo is such that the spot could very well be re-located by an on-the-ground fix, referencing from the terrain beyond (Popes Nose/Moncrieff?) aided possibly even still now by the bush profile shown in the foreground.

Possible fuselage sighting

On their final day, the three men clambered down through high tree cover. They came across a moss-covered shape that they thought bore an uncanny resemblance to an aircraft fuselage. The terrain was rough, they were exhausted after having spent several days at it, were fighting tough scrub, and were anxious to get down and out. Greenlees, now after 20+ years, only vaguely remembers it. But they were conscious of the fact that that was the sort of thing they had been looking for. They were keen to get down and meet their helicopter and unfortunately had neither the time nor energy to investigate the strange shape.

Harnett’s comments on location

Harnett recently provided a marked photo (photo supplied by the writer - then marked by Harnett). Harnett commented -

“Have marked up as best I can remember where our searches occurred. That was our camping area as you've shown. Its very hazy my recollection so its not gospel obviously the area I marked as possible fuselage shape sighting. I remember roughly what height we were because I was looking down at the campsite, it would of been lower than that x marked if anything. I was looking through the tree canopy and could see the campsite area. Don't think we went into that gorge as it would of been too steep possibly.The shape was kind of a tapering fuselage shape covered in thick moss.”

As marked by Harnett -

Greenlees’ comments on location

Greenlees has viewed the above photo now marked by Harnett. It fits his memory of where they were, as best as he can now recall after 20+ years.

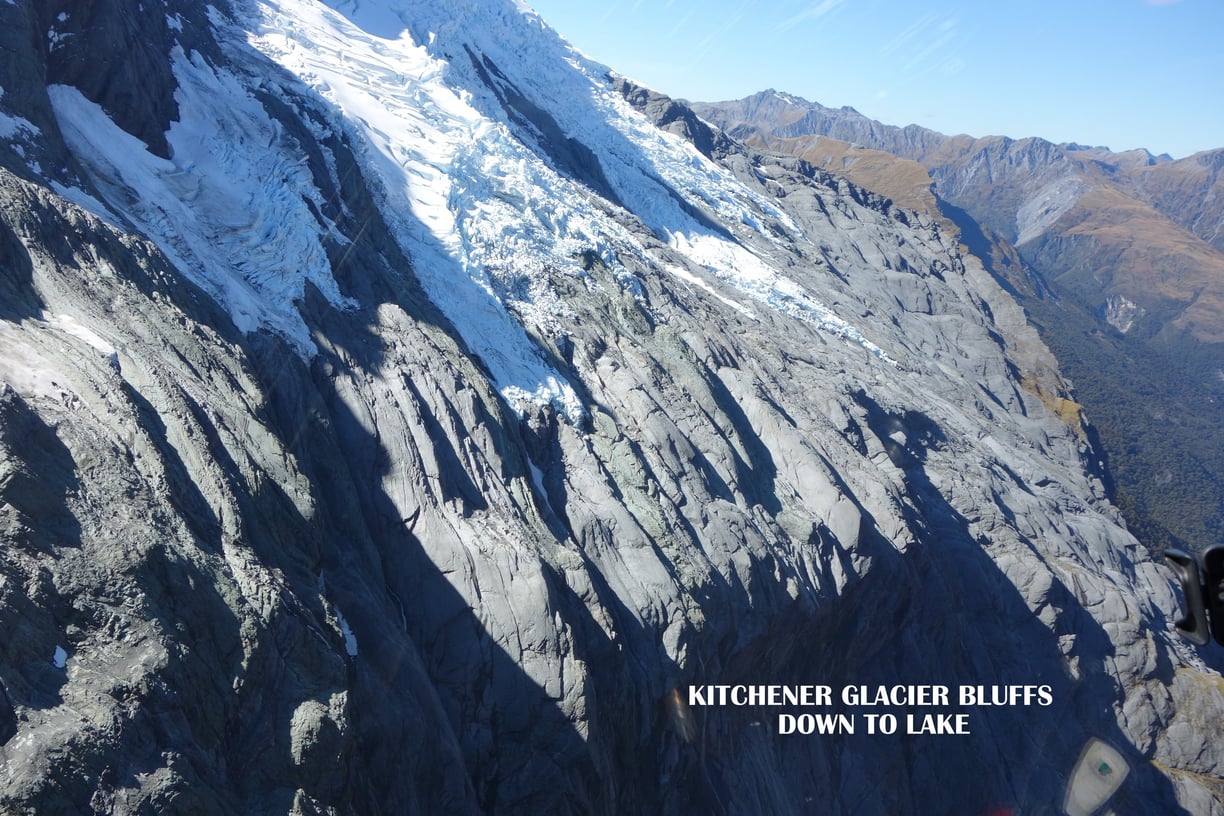

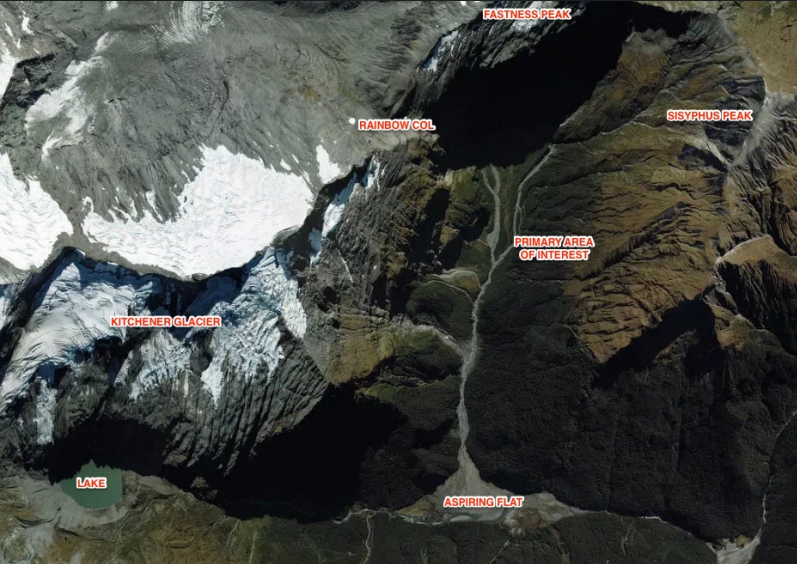

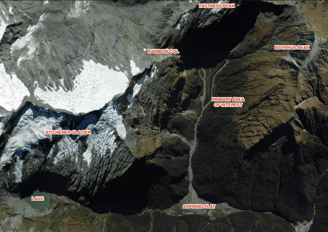

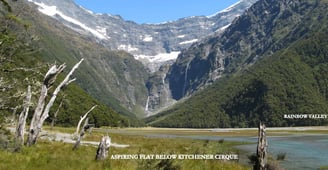

Rainbow Valley - possibilities?

The Rainbow is a confined valley running roughly North/South below Kitchener and Lucas Glaciers and the peaks of Pope’s Nose and Moncrieff. It is prone to avalanche on its west face. In 1969 four university students were killed in an avalanche at the northern end of it. A large glacial snowfield slopes down towards what is Rainbow Col - a low gap between peaks, situated at about 1700m elevation with near vertical bluffs plunging down to Rainbow Stream. The valley’s name derives from the rainbows that can be seen in the waterfalls that cascade hundreds of metres down into the valley. It can be a beautiful but hazardous area to wander in, best done on the east side of the valley away from avalanches from above the bluffs.

Some years prior to the Dragonfly’s disappearance the aircraft had been repainted. In 1962 it was mainly silver-blue in colour. It’s earlier overall main colouring however had been a bright orange, for purposes of coast watching during WW2. One person familiar with the aircraft has said that despite the new over-paint, some underneath parts - possibly cowling/nacelle or spats, (all alloy) were still orange, the same prominent colour as the metallic object seen by Cowie and King.

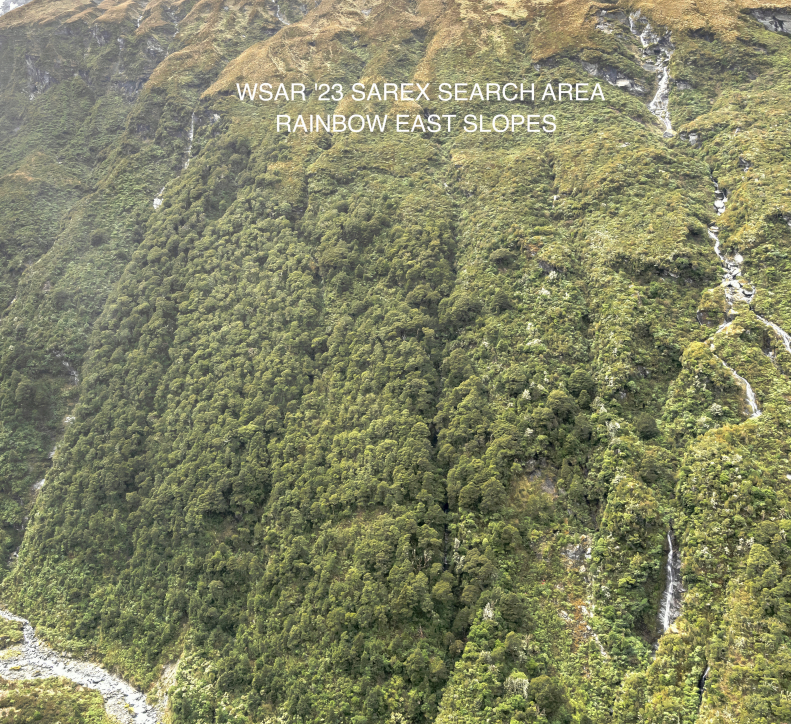

From all this, one possibility could be that perhaps the Dragonfly had been lost in the thunderous cloud described by people at Mt Aspiring Station, perhaps inevitably coming down on a single engine, and had collided with peaks by the glaciers, resulting in some part of it coming off from where the aircraft continued down into the opposite east side of Rainbow Valley, a rugged area covered in bush, scrub and ravines. Three (amateur) searches in that area in the 1990’s found nothing. The area is covered in very tall beech trees, in places almost impenetrable bush, and ravines.

Chadwick and other mountain pilots always sought out areas where emergency landings could be made. Aspiring Flats, immediately below these glaciers, is a large flat area that could be landed on in some conditions. Rainbow Stream fans out and flows into the Flats.

It is perhaps possible that a small part of the aircraft had dropped on to this glacier top (to be seen 6 weeks later by Cowie and King), with the aircraft descending down across Rainbow Valley into the rough terrain high on the east side.

Other possibilities have also been presented. A former pilot, the late Paul Beauchamp-Legg, had flown this aircraft many times and knew it’s engineering and handling characteristics extremely well. Amongst many observations he said that this aircraft in high turbulence would be - “like a piece of paper in the wind”. The relevance of that is discussed below.

Since the 1990’s, no new information had come to hand and the mystery, and any theory about Aspiring, was largely left to rest. Over Xmas/New Year 2020 a private review of an Aspiring scenario was carried out. The sightings in the 60’s by these three very credible people, all of whom had agreed in the 1990’s to revisit the area and re-enact what they’d seen, coupled with Duncan’s 1972 report, left a convincing possibility that something had occurred in the area. But what? Part of the scenario was troubling in that Bob Gibson had seen something relatively fresh, yet this had been 20 months after the disappearance. There was some difficulty in connecting what was an obviously manmade object being seen on a glacier or snowfield six weeks after the disappearance, with something being seen across the valley a full 20 months later, yet described as “fresh”. Faced with those seemingly conflicting accounts, was there another possibility?

Lingering too was Paul Beauchamp-Legg’s earlier description of how any part of this aircraft could easily be carried across this valley in conditions of northerly storm and turbulence. Dramatically picturesque as it is on a nice day, the glaciers and rough terrain high above the (opposite) western side of this valley can be frequently subject to violent wind storm, turbulence, updraughts and downdraughts, with wind so strong it can be impossible to stand up in. Updraughts occur on the upwind side of mountains and downdraughts often with extreme turbulence can occur on the downwind side. These can occur in all conditions, due to many factors.

So it's not impossible that all of what was left of this lightly constructed aircraft actually remained spread over an area near Kitchener Glacier (Cowie/King sighting) or the western tops, which are all subject to yearly snow avalanche, with a wing section (it had four wings) some time later dislodging and being carried across the valley, months after the crash during spring thaw and the notorious north-westerly storms that can prevail, thus accounting for the freshness in the tree breaks on the east side, and then Alan Duncan's sighting some years later? If that happened, any remaining debris would probably have moved off the tops and down into the craggy bluffs below. However, all of that is highly speculative, and perhaps a little contradictory. Over 63 years there has been no debris sighted or other evidence of a crash on the western side of this valley.

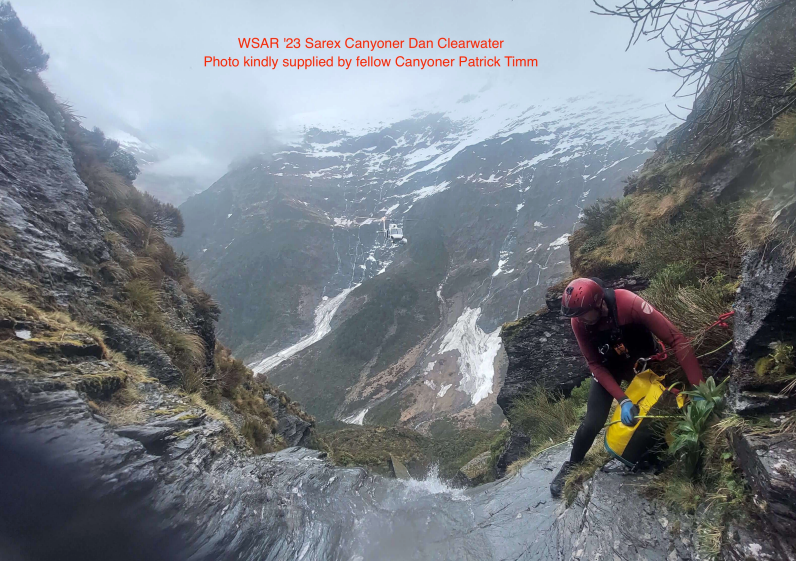

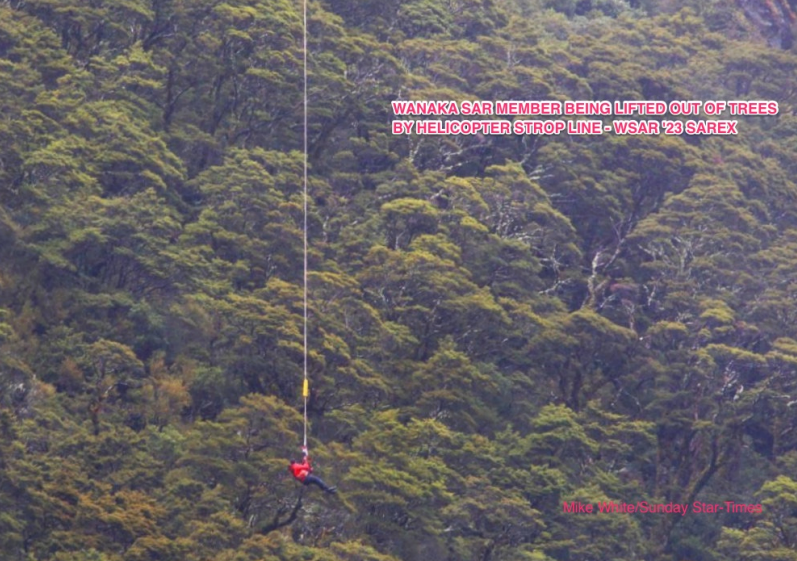

Wanaka Search & Rescue - 2023 SAREX

In November 2023, Wanaka Search & Rescue carried out a search exercise (“Sarex”) in Rainbow Valley. The exercise focused on the Dragonfly, aided by certain highly technical data anomalies that provided some gps coordinates of possible points of interest. Nothing however was found at the coordinates provided. Expert interpretation of the technical data is still under evaluation, but in retrospect the preliminary feeling is that the supplied data anomalies may have been derived just from natural features such as large buried boulders. The exercise on the day well illustrated the considerable challenges with ground searching in that terrain. The steep slopes contain hazardous watercourses and much of the area is not for amateurs to attempt to traverse.

The area indicated by Greenlees and Harnett is consistent with Reinke's description of the location where Gibson in 1963 saw a reflection from the valley floor and on investigation found two trees broken.

Gibson’s account of this might well tend to suggest that whatever caused the breaks came down from the direction of Sisyphus slopes above, with the other tree break further down being a secondary (final?) impact point. This is an admittedly speculative assumption, but a reasonable possibility based on his description.

This area of defined terrain interestingly also additionally closely fits the description given by Alan Duncan of where he saw "a wing" (or perspex) on the tops in 1972, just above the then bushline, with a rough gorge running up to his right.

There are precedents for aircraft of De Havilland construction that have come down in a high tree canopy, for cables and wood etc to be left visible in tree tops, for decades. This valley experiences ferocious gale force winds from the north-west. It’s not unreasonable to speculate that the wing seen by Duncan in 1972 might have separated from the fuselage on first impact with tree tops and over time had been blown a short distance back uphill from that initial impact point? That possibility might account for the 2004 finding by Greenlees team at bushline of what might well be a broken off section of the wing section stub plane spar, although terrain factors (near-vertical high bluffs along the upper areas) could tend to negate that kind of scenario.

All of this information, based on assessed credible historic interviews and now very recent new inputs, provides a complementary evidential overlay suggesting there is aircraft debris within a defined area of the terrain more widely shown here -

Conclusions

There is now a body of plausible assessed evidence suggesting that there is aircraft debris waiting to be refound on the eastern slopes of Rainbow. It stretches belief that all of the now numerous supporting reports, and the chain of evidence they present, are collectively merely coincidental, or mistaken, or are of something non-aircraft related. There had been no other aircraft missing either in this area or anywhere near it. There is no reasonable basis for there being any manmade objects, somehow discarded or perhaps dropped from some other aircraft, to be left laying on these remote and difficult slopes.

All of the evidence, taken as a whole and by reasonable elimination, consequently point to it being debris from the Dragonfly. Additionally, a strong possibility exists that whatever remains of this aircraft and its five occupants may well still lay hidden, under difficult to access tree canopy, in an area now reasonably defined and coincidentally or not adjacent to the 2023 Sarex area. The acceptance of what are two separate reliable reports - that of Duncan’s 1972 “wing”, and in 2004 the Greenlees party’s wood, and taking into account Gibson’s 1963 sighting of something shining and viewable from the valley floor, with two broken tree tops, all would tend to support the scenario of a likely progression from the rough direction of Sisyphus, down into trees.

Over a period of 63 years there have been no reports providing verifiable or reasonably assessable evidence of a flight termination anywhere other than in this area. From all of the various individual inputs provided and now described here, none negate this scenario. Instead, all have, perhaps tellingly, built to support it.

The area is now Department of Conservation administered land. The challenging terrain and alpine weather suggests that any contemplated ground searches should be professionally managed, and carried out in favourable conditions.

The writer welcomes any comments via email to lewbonenz@gmail.com.